Over the centuries, flesh has enticed artists of every kind — painters, sculptors, and photographers — to capture its essence. From the Venus of Willendorf to Lucian Freud, artists have responded to call, depicting every part of the human body, from the infirm wattle of an old man’s turkey neck to the taut muscles of young boys in Caravaggio paintings.

And now flesh is the subject of a big new exhibition, Flesh Art, at New Jersey City University (NJCU). The show is curated by NJCU art history professor José Rodeiro (at right), and it features the work of 12 artists, including Joan Semmel, Ben Jones, Babs Reingold and Jen Mazza.

“The premise of the show is that human flesh can be an aesthetic motif on its own,” Rodeiro says. “I hope that those who attend the exhibit will leave with a renewed perspective on what flesh is and what it can mean.”

Rodeiro told us more recently as he made some final preparations for the exhibition, which has its opening reception this Thursday.

Tell us more about the show, and how it came about.

I first became involved in Flesh Art by viewing and considering the artworks and the ideas of Matthew Lahm, when he was still one of my graduate students. His extraordinary work and ideas intrigued me.

For example, at the current show, you will see a ten-foot painting called Body View 1, which depicts part of a human body. By only showing a small part of the body within ten foot surface, the image is utterly mysterious, because the model’s identity, gender, and the actual part of the body displayed are unknown. Through this unusual “hyper-figurative” approach, the flesh itself becomes the subject of the work.

Suddenly, I realized that Lahm was part of a coterie of urban artists who used flesh/skin as their primary subject matter via this ambiguous visual-artistic handling of the body that I called “flesh art;” I began to notice a trend in contemporary metropolitan-area figurative art traceable to pioneers like Joan Semmel.

In the early 1970s, Semmel created innovative flesh-based paintings, which made her a pivotal figure in the development of flesh art. She seems to have influenced numerous artist like Lahm, Coronado, Cruz, Sandra Silva, Mazza, and Rogeberg, and others, whose images echo many tendencies found in her work. We are fortunate to have three never-before-seen paintings by her featured in the show. Flesh Art points to what I think is an evolution in 21st Century figurative art and where it can go in the future: amplifying parts and fragments of figures as subjects in and of themselves.

What is attracting this new generation of figurative artists to investigate flesh, and why now?

Perhaps it is that cosmopolitan artists feel that their core humanity is under attack from hyper-technology, fanatical dogmas, war, economic uncertainty — and perhaps that art itself is under threat.

Who is in the show, and what can viewers expect to see?

I have already discussed Joan Semmel and Matthew Lahm. Also featured are NJCU’s eminent retired professor Ben Jones, who is a prominent figure in African-American art, and NJCU professor and acclaimed sculptor Herb Rosenberg. The exhibition includes works by Rutgers professor and internationally active painter, Hanneline Rogeberg. There are strikingly visceral installation and multimedia works by Babs Reingold of Bayonne; intimate oil paintings by Jen Mazza of Brooklyn; cityscapes incorporating flesh in media by acclaimed painter John Hardy of New York; and video art by Giuseppe Satta of Italy. Furthermore, there are exceptional and distinctive images of human flesh (and innovative flesh-based compositions) by three other exceptional and gifted emerging artists (and like Lahm, NJCU alumni) Williams Coronado, Sandra Silva and Olga Cruz.

As soon as I heard the title of the exhibition, Flesh Art, I pictured the painting Woman, 1, by artist Willem de Kooning. When I mentioned the name of the show to my girlfriend, she assumed it was of tattooing.

This is merely my own aesthetic-opinion, but I do not immediately think of human flesh or skin when I see de Kooning’s Woman, 1. De Kooning’ s paint-application is very sensuous, which is the only thing about his work that I consider to be fleshy.

Honestly, tattoos are not an issue in the current Flesh Art show, because tattoos modify, hide, or visually change flesh and skin. Thus, tattoos tend to transmogrify, decorate, camouflage, or they add ancillary symbolic iconological meaning to skin, which distracts from the actual tone, texture, and fleshiness of “natural” skin or flesh.

I had another thought nipping at the heels of Woman, 1, and it was pornography. “Flesh Art” sounds dirty, and I ashamed of myself for thinking in this manner. As an artist, I like to think of myself as progressive, tolerant, and open-minded — but occasionally I am not. Did you intend the title of the show to be provocative or am I way off base?

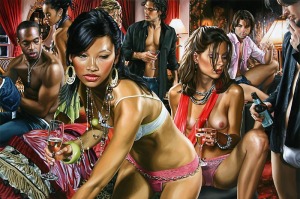

The original intention of the Flesh Art show was never to be pornographic or provocative, [but] it could come across that way because flesh can be so taboo. The title is merely descriptive and represents 12 exceptional artists who exalt in seeing and depicting human flesh — artists who are fascinated by human flesh – as human flesh. In my opinion, none of the selected Flesh Art artists pander to prurient interest nor do they endeavor to arouse lascivious curiosity.

So, according to your definition, flesh art would not include painters such as Lisa Yuskavage, Terry Rodgers, and John Currin? Am I correct?

Yes, because flesh art is far more concerned with mysterious parts of bodies, instead of full-figure grand-manner depictions. Flesh art is not concerned with scintillating and pseudo-pornographic calculated depictions of hyper-seductive, manipulated, erotic and embellished dehumanized figures.

The nude is the foundation of Western art. However, as an Irish-Catholic male born and raised in a modest ranch house in New Jersey, I am not wholly comfortable with the human body in a state of undress—unless I am watching two men inflict and take punishment inside a boxing ring. What do you hope the viewer takes away from the work in this exhibition?

Within the context of art history, representations of human figures in the nude or naked are recurrent subjects. In fact, the history of art is saturated with astounding depictions of flesh from Classical Greek and Roman antiquity; Hindu and Buddhist artistic traditions; or as exemplified throughout Western art from the Renaissance onward. As a theme in art, unclothed human subjects are widespread and rooted deep in art history.

The artworks in the Flesh Art show describe the body as a medium through which the mind thinks and feels. As a result, flesh art imagery presents human skin/flesh as a layer through which the human body meets the world in which it lives. Hence, according to this view, people (in every way) truly inhabit their skin. Moreover, on a visceral level, both affectionate people as well as sadists are drawn to flesh, erotically desiring the skin of others. Therefore, both the human body and its flesh are noetic or intuitive vehicles for processing and possessing existence. Thus, skin functions as a “self-reflecting” subject that reaffirms and embodies the self, as a mirror image of our “being.” As the old-adage warns, “Beauty is only skin-deep.” Likewise, skin — as the largest organ of the human body — encases the body.

Art history is stacked with men. As a viewer, I have usually seen flesh — usually the flesh of nude women — depicted by male artists. Do female painters approach the body in a different manner than their male counterparts? If so, what does their work communicate about the body?

The old distinctions and obsolete hegemony between male artists and female artists are not central to contemporary flesh art, since most 21st Century urban pioneers of flesh art have been women artists. Yet, the key issue is that flesh art does not depict the full grand manner figure. Despite historical figural traditions that reveal nude or naked human bodies from head to toe, 21st Century flesh art images often portray only portions or sections of human bodies wherein strong emphasis is placed on ample corporeal surface-effects that meticulously define each body’s accentuation of flesh (or skin). Generally, the sheer veneer of flesh is not the main aesthetic focal point; instead what is often stressed is the exterior fascia, revealing a modular or sectionalized surface façade that may well be smooth, sinewy, vivacious, undulating, rough, coarse, or expressing countless other surface possibilities (even within one piece). Consequently, each work offers a crucial section of a human being’s body.

De Kooning once said, “Flesh is the reason oil paint was invented.” For me, oil paint is particularly suited to capturing the vivacity of flesh. However, not all artists use oil, and not all artists paint. Artist Babs Reingold is featured in the exhibition. She has used encaustic, silk organza, animal skin and human hair in her installations. What can other mediums communicate about flesh that oil paint cannot?

The diverse artists exhibiting in the Flesh Art show do not exclusively rely on oil paint to attain their facsimiles of flesh or skin, although several do use oil paint. On the other hand, the show also features artists working with charcoal on skin, scratching and machining onto aluminum, using photography or doing wet-acrylic colorfield-painting like Ben Jones — or like Babs Reingold, using encaustic, silk organza, animal skin and human hair. The multimedia nature of the show broadens the artistic examination of human flesh on many levels.

Art has the power to reveal our uneasiness about the body. Does art that reveals our uneasiness about the body have the power to heal it?

I think there is an element of redemption of flesh in this NJCU exhibit, in that flesh art liberates the nude from social presuppositions, prejudices, and peripheral narratives that can taint our points of view about it. Flesh Art shows how artists can communicate a variety of meanings through flesh, which are simultaneously experiential and conceptual. Human skin/flesh is our connection to the world and — as a person living in the world and as a person devoted to art — pondering the significance of this “natural” bond to me is valuable and worthwhile.

Original post may be found here.